Opening: 23 January 2024, 6PM

Opening speech by Judit Árva

“Who are the pampas?”, asked a little girl (who was not me) a good thirty years ago.

A South American tribe, replied her dad (who was not my dad).

I don’t remember what The King of the Pampas was about, and I stopped to look it up. And you can also stop here to look, you don’t have to read everything.

Grant Wood, later to become an American Gothic painter, traveled to the decadent region of Europe, Weimar Germany, in 1927 to create what he thought was self-identified American art, a regionalism free of decadent European influences, from the lessons of the New Objectivity. For the rest of his life, he insisted that his ironic paintings were objective, free of the irony that characterised New Objectivity. But regionalism was already present in his last major work before his departure: he painted a pasted panel of what he saw as the soul of the Iowa landscape, a cornfield, on the four walls of a hotel lounge in Sioux City. The fate of the painting is as controversial as that of his later work: it was painted, pasted down, forgotten, and then parts of the peeled-off image were lost. Viewers of the restored remains in the museum today are confronted with a radically altered vision: the colourful, popular panorama has been transformed into golden, almost monochrome fragments, as if the notion of landscape and the landscape itself were breaking down its own framework.

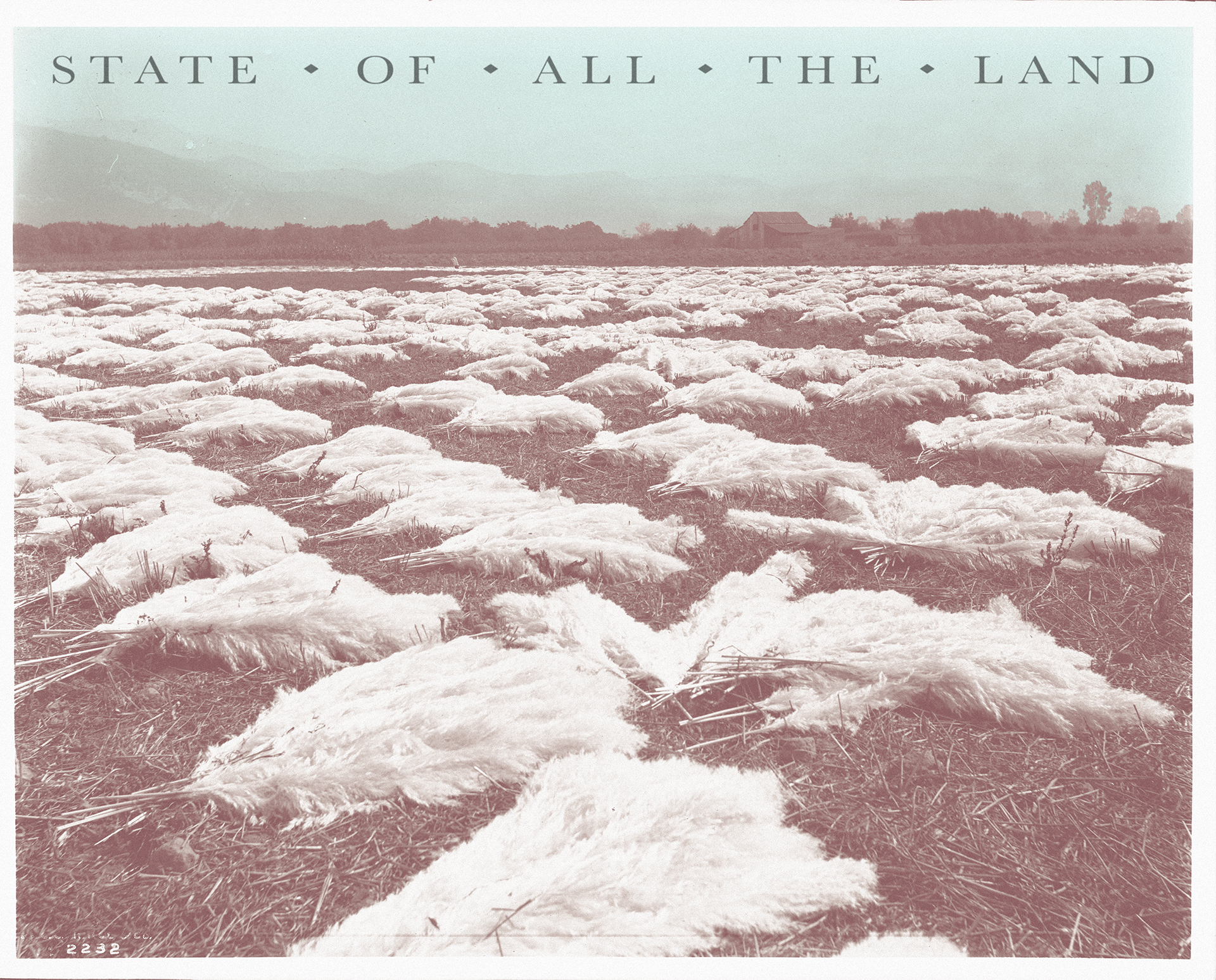

“State of all the land,” praises the land the Iowa Corn Song, the cover of which Wood took as a basis, but has painted “Best in All the Land” as the motto above the panels. The myth of the ‘landscape’ as a ‘national landscape’ is always partly constructed. The dynamics of ancient and foreignness, conservation and adaptation, are complex. Alan Sonfist’s famous Time Landscape, an urban parklet reconstructing the pre-colonial East Coast flora, can be classified as critical art, but it can also be interpreted as a phenomenon of eco-xenophobia that re-enacts the invariability of the ‘eternal’ landscape.

The (invasive) plants that alter the landscape can be both useful plants and (former) ornamental plants that have lost the exoticism of their ecological success in their new habitat, such as the now-eradicated Japanese knotweed, which was once a special ornamental plant. The big exception is the pampas grass, a sought-after ornamental plant in many places, including Hungary, but is considered an invasive pest in many places.

The name actually covers two variants: the Andean purple pampas grass, Cortaderia jubata, which was once introduced from South Africa to New Zealand for soil conservation or forest protection because of its sharp foliage, but is now banned in the EU, alongside Cortaderia selloana, which is native to the pampas. Selloana was grown in California from the 1870s in endless rows like maize for its impressive plumage, and was exported worldwide as a hat and vase ornament, decorating horse-drawn carriages at flower carnivals before becoming a garden ornament. In Iberia, the plant escaped from the gardens of luxury villas built near abandoned areas and has been banned there, but its status is being investigated throughout Europe as it spreads due to warming temperatures. In Maui, the pampas grass populated lands left empty after the decline of sugar cane and pineapple plantations, which were introduced as a cash crop and destroyed the island’s natural ecosystem, but unlike on the eponymous island of Hawaii, in Maui it has not been eradicated. The oily inflorescence of the pampas grass promotes the spread of fire, while its wicks survive it, making it a beneficiary of fires. That’s why the recent Maui fire sparked a debate about the role of pampas grass (and other invasive plants), global warming and exceptional drought, although it seems that human negligence was the main factor this time.

Grant Wood’s murals use the simple motif of maize to encapsulate a millennia-old agricultural culture and the history of territorial domination. Where pampas grass spreads, it takes on the monocultural character of endless cornfields or other plantations. But there is no landscape for pampas grass – or rather, the whole world is.

Kitti Gosztola

On the Land of Constructed Terrains

This text was read at the opening of Kitti Gosztola’s exhibition State of All the Land at Kisterem, on 23 January 2024.

‘Around the building there is nothing but emerald pampas grass running to the horizon. Like a steaming cruise liner moving forward on a steel-grey body of water, the station is surrounded by grass and grass. The deep green, heavy-scented grass, swaying in waves, somehow vividly evokes the other ocean. This too, is infinite, eye-boggling in scope, mysterious and enigmatic, fragrant and variegated in colour, enchanting and soothing.’[1] – wrote Rezső Péchy-Horváth, writer and journalist, in the Pécsi Napló in January 1927. The poetic, lyrical tone belongs to a – presumably – fictional travelogue, with created characters and stories, somewhere in South America. One of the main characteristics of the imagined place is the silky swaying of the pampas grass, which gives the landscape a particular colouring. The plant itself suggests a broad sense of locality; the apparent authenticity of the description is due to the plant’s territorial, a kind of ‘national’ character, which is also implicit in its name, pampas grass. There and then.

In her present exhibition, Kitti Gosztola critically questions the situation of this plant with her usual depth, yet in an unusual way. The velvety-looking plumps of the now common pampas grass, known as the ‘queen of grasses,’ are sometimes used as decorations or ornaments in gardens, while in other places, where the plant is not wanted, the mere transport of the seeded inflorescence is prohibited.[2] The artist explores this ecologically problematic relationship, in both cases constructed by humans, with a reference and central analogy of an equally ambivalent work, Grant Wood’s Corn Room.[3]

Grant Wood was a prominent figure in American regionalism, a modern art movement based on rural and small-town settings. He was also the only internationally known artist from the state of Iowa. Wood painted four murals commissioned by hotel magnate Eugene Eppley for his four hotels in the second half of the 1920s. One of them was for the Martin Hotel in Sioux City, which was completed in 1926.[4] Wood’s Corn Rooms served to promote the countryside and agriculture, and also to ‘glorify’ a crop: the subject of the works is corn, which has become emblematic of the Iowa landscape. It has become so artificially; Wood has placed the plant at the centre of his several works, which were ‘coloured’ by both business interests and ties to corn breeders.[5] The dimension of the mural that once occupied the entire wall of the dining room of the Martin Hotel, reminiscent of mythological or historical wall paintings by its grandiosity, the systematic nature of its theme and details such as the inscriptions or the chandelier ending in corncobs, gave the impression of an unusual place of worship.[6] The corn, the basis of Iowa agriculture, was given a new image and visual representation; the perfect ears of corn in many of Wood’s works were the result of hybridization and standardization in size and weight.[7] The later history of the work is less filled with pathos: it was covered with wallpaper in the 1950s and only in 1979, following an interview with Wood’s assistant, was its existence rediscovered.[8] As a result of the restoration, the mural is now on display in pieces, heavily fragmented and deteriorated, in museum settings at the Sioux City Art Center. The result of this transformation has a curiously sacral overtone. The mysterious, gleaming golden fragments, connected by a horizon line, make the museum space look – absurdly – like a chapel; but the object here, unlike religious subjects, is a crop.

In Wood’s work, landscape, plant and national character were merged, as was frequently the case in 19th century landscape painting, where these concepts were also intertwined.[9] The character of the term ‘national’, an often pejorative concept these days, could be seen in the clothing, the behaviour of locals, or even in vegetation. As art historian Katalin Sinkó noted in connection with the landscape paintings of the Great Hungarian Plain, ‘… it is about the nature of the inhabitants of the landscape as well as of its flora, in connection with it is also revealed that the favourite plant of the Hungarian people – like the oak of the German (…) – is the European feather grass blooming on the plains!’[10] (It is interesting to note that in Hungary in the 1960s and 1970s, the pampas grass, which could only be found in botanical gardens, was compared to the feather grass.) The image of the grass swaying in the plains is as idyllic and romantic as Grant Wood’s Corn Room; the association and the connection, though based on real grounds, are nevertheless constructed. The plant as a social construction, i.e. the assumption that each plant bears the marks of a particular society or community and its interventions, is valid in both cases.[11] This is also true of the pampas grass, which has spread outside its original habitat through human intervention, both intentional and unintentional, and has become a ‘world citizen’ rather than a guest.[12] If it has lost the character of its place of origin, what kind of landscape can this plant inhabit? This is the question that Kitti Gosztola addresses in her present works, where she balances possible answers on the edge of real and constructed landscapes.

The artist has worked with plants that are both commonly known as pampas grass, but of different subspecies: the whitish Cortaderia selloana, native to the Pampas, and the pastel purple Cortaderia jubata appear in the watercolours. The latter, despite its characteristic silky colour, is banned throughout Europe because of its invasiveness. The status of its companion is still in question; its silvery ‘plumage’ is still cultivated for decorative purposes, albeit on a much smaller scale than during the 20th century. The seven works on display in the exhibition spaces are inspired by the places where these two species occur: in the foothills of the Andes, on a roadside in Maui, or in endless, regular rows in a Dutch plantation. Behind each of them is a specific story, a source of information on the plant’s characteristics, such as soil retention or invasiveness, which testifies to the researcher’s approach of the artist. At the same time, Gosztola’s landscapes are distanced from their origins and are difficult to differentiate; the systematic use of layered pink and sandy tones blurs the boundaries between landscape units, creating a constructed landscape that appears identical. This landscape is also fragmented, like the one of Grant Wood’s Corn Room; only the horizon line connects the pieces, the gap between them left for the viewer to fill.

The watercolours have a special atmosphere. In some cases, the triptych-like arrangement gives the works a religious tone; only the pampas grass with its pure white plumes stand out from the monochrome, sometimes hazy surfaces, that play with so many shades. In another approach, the ominous turquoise skies suggest a less than ideal future. Silvery, sometimes copperish pearly details evoke grains of sand, drawing attention to the global ecological problem of desertification. The works can be interpreted as metaphors for human intervention and arbitrariness, as can their chosen counterparts, the fragmentary mural panels of the Corn Room. Kitti Gosztola has thematised the act of human destruction in previous works, such as in her series Right Tree Right Place (2013-2014), where she memorialised trees that had been mutilated due to the construction of power lines. The vision of the present series, however, is much more visceral. The paintings, with their worn tones, faded hues and fragmentation – obviously references to the artist’s main source of inspiration – look from here like remnants of a bygone age, relics of a possible future. They are traces of a present that will be worn away by time. What kind of landscape, what kind of future would the pampas grass be emblematic of? How would a generation of this future view the plant studied and thus highlighted by the artist? Is its invasiveness not bound to make it lose even more of its local character and create a landscape constructed by it? The answer may no longer be up to us alone.

Judit Árva

[1] Péchy-Horváth Rezső, ’Marsá-Falset (From my South American memories.)’ Pécsi Napló, 16 January 1927, p. 6. Highlighted in the original text.

[2] Pampas Grass. Invasive South Africa, https://invasives.org.za/fact-sheet/pampas-grass/ (Last accessed: 21 January 2024)

[3] The artist herself mentions the reference in the text of the exhibition.

[4] Grant Wood’s Corn Room Mural. Exhibition text. Siuox City Art Center website, https://siouxcityartcenter.org/exhibition/grant-woods-cor7n-room-mural/ (Last accessed: 21 January 2024)

[5] Travis Earl Nygard, Seeds of Agribusiness: Grant Wood and the Visual Culture of Grain Farming, 1862-1957. University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, 2009, p. 184-190.

[6] A photo showing the interior and the corn chandeliers can be seen in the presentation of Kenneth Be’s 2011 lecture, from 13.24: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iDfRRx7mP90&t=614s (Last accessed: 21 January 2024)

[7] Nygard, Seeds of Agribusiness, p. 189-190.

[8] Grant Wood’s Corn Room Mural. Exhibition text. Siuox City Art Center website, https://siouxcityartcenter.org/exhibition/grant-woods-cor7n-room-mural/ (Last accessed: 21 January 2024)

[9] Katalin Sinkó, ’Az Alföld és az alföldi pásztorok felfedezése a külföldi és hazai képzőművészetben’ [The discovery of the Great Plain and the shepherds of the Great Plain in international and local art] In Katalin Sinkó, Ideák, motívumok, kánonok [Ideas, motifs, canons] Hungarian National Gallery, Budapest, 2012, p. 206.

[10] Ibid, 211.

[11] Nygard, Seeds of Agribusiness, p. 183.

[12] Tibor Hortobágyi, ’„Bennszülött”, „vendég” és „világpolgár növények hazánk földjén’ [“Native”, “guest” and “ world citizen” plants on the land of our country.] Élet és Irodalom, Calendar, 1969, p. 240-246.

photography by Barnabás Neogrády-Kiss