Flash Art Hungary 2012/5

The Latest Geometry

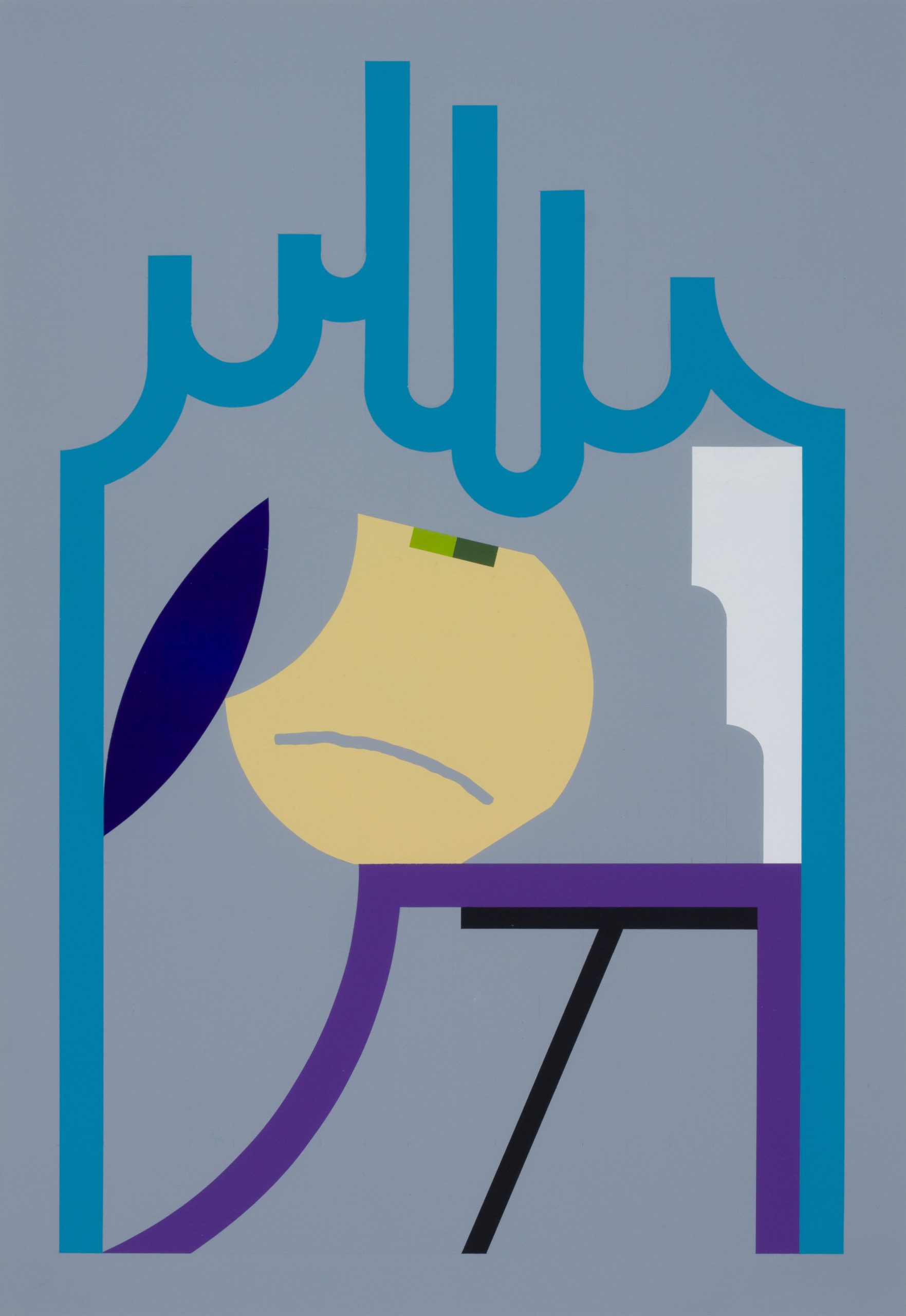

Gergő Szinyova is a recently graduated young artist, whose work connects to the current international trend of abstraction and reduction: pure basic forms, extreme noises, the aseptic world of an engineer. The majority of his works are acrylic on paper, mostly in two dimensions. This winter, however, he is about to come up with constructions of wooden battens that step out into three-dimensional space. His airbrush-works explore the kinds of traces airbrushes can leave, while his RGB-series is a system of monotonous lines drawn with felt-tip pens, the points of which have been cut. While working, he usually listens to contemporary experimental electronic music. What inspires him most in this sort of music is its relation to abstraction. “I do not hear the term ‘abstract music’ very often, ‘experimental’ is a more common term; however, these two things seem to be related” – he says, commenting on his theory of contemporary music. “If something is experimental, that must be abstract as well somehow.” The recognizable experimental contingency of music appears foremost in his sketching process, while repetition becomes a guiding principle of his formal systems. This is well illustrated by his striped works employing red, green and blue felt-tip pens. According to Szinyova, “the RGB-series is the result of an interesting experiment. From my set of colour pens, I always used only the black one, so finally I ended up with all these red, green and blue ones. I kept drawing lines with them with great vigour, but they still wouldn’t run out. In the background there is loud experimental contemporary electronic music, and I draw these lines in a static way, following the rhythm, repetitively, acting like the recurring beats of the music.”

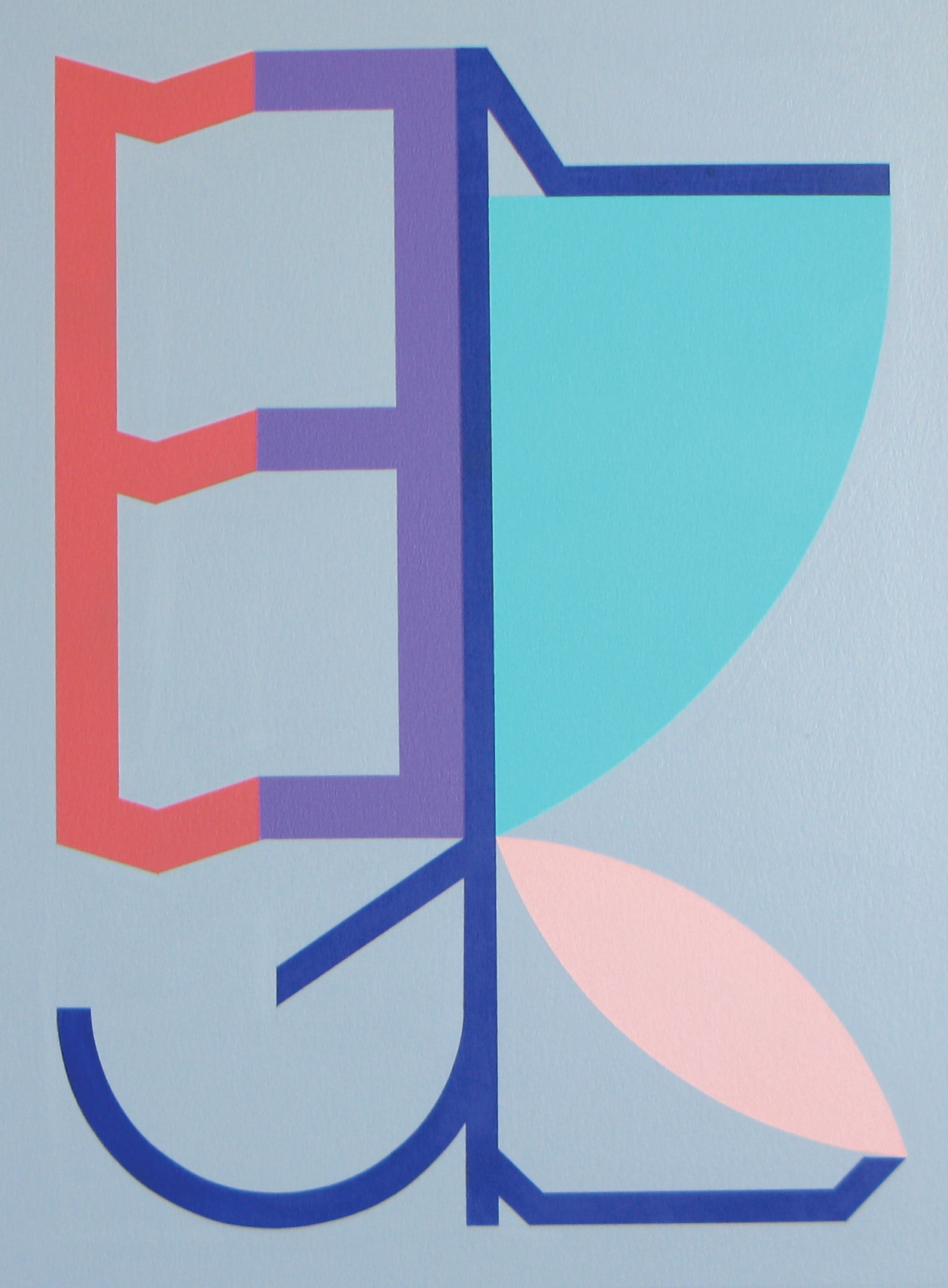

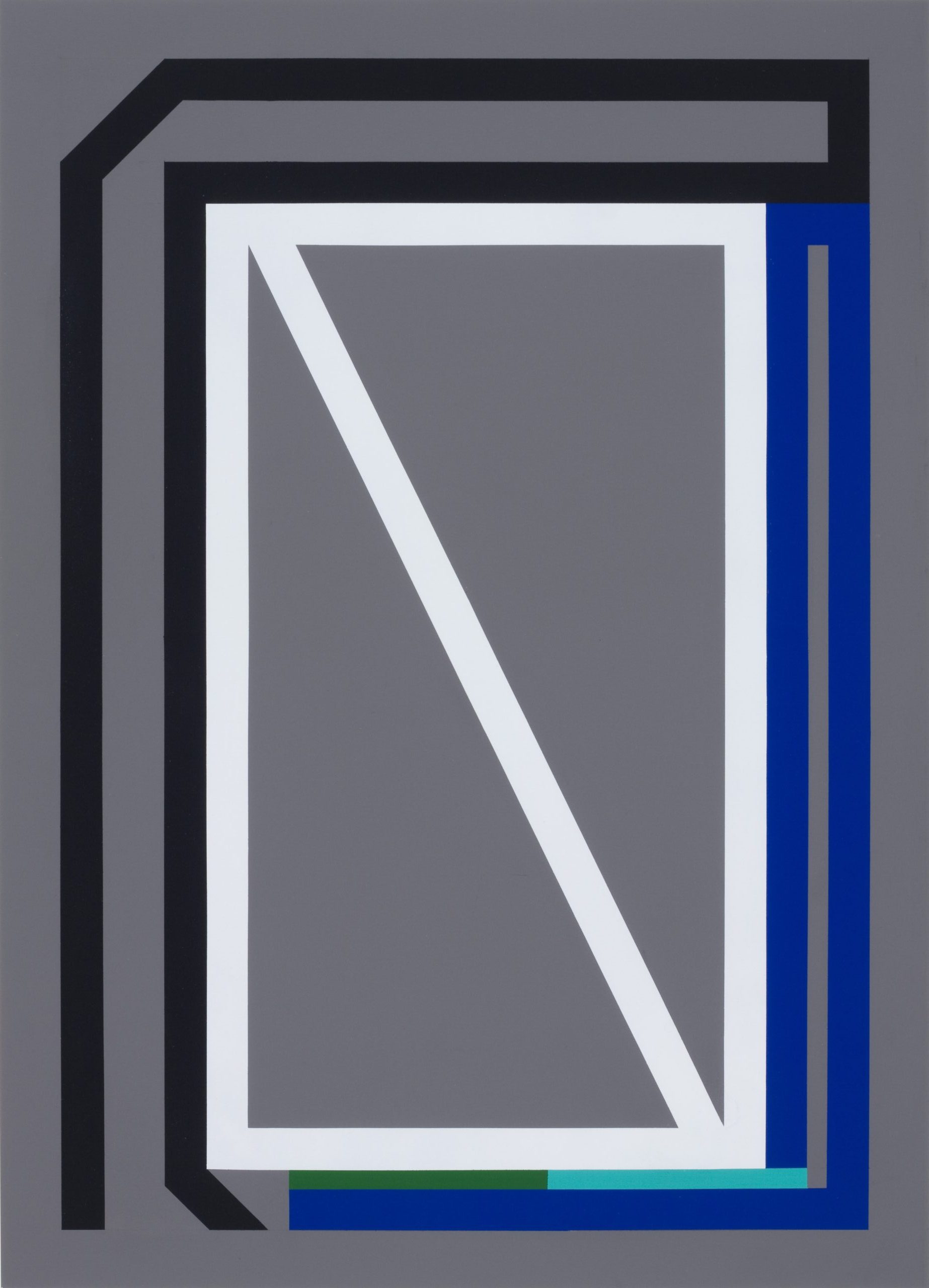

With his colour works, Szinyova replaces this passionate attitude by a methodical approach. He measures each and every colour-streak, constitutive of the structure of the work, to the millimetre; then he covers and paints each field with a roller. This kind of universal and academic geometrism is unique in Hungary. This geometric approach is present in Hungary like a sinusoidal wave: it disappears from time to time so as to reappear again, out of nothing, with new representatives. Szinyova’s work connects mainly to abstract tendencies overseas and in Western Europe, more specifically to the “new abstraction” practiced in Denmark, France and Switzerland. These works that are built according to the pattern of an algorithm (repetition, variation, combination), and are made of all sorts of materials (glass, textile, adhesive tape) are purely self-referential, without any thematic content. Bastien Aubry and Dimitri Broquard, Jeff Depner or Tauba Auerbach are among those numerous artists who apply a grammar of pure forms, surfaces, colours, materials and patterns, independent of time and place, without story or emotions.

“I express my respect for the pioneering artists who worked in the same genre by trying not to plagiarize them, by not repeating the same.” The very same idea is expressed by the title of his 2011 publication that also includes graphic constructions and photos: his project The past doesn’t have to control your future shows his abstract drawings inspired by the geometrical forms of the frames of advertising billboards left on the rooftops of apartment blocks in Budapest.

His systematic zeal also shows in the way he regulates himself and defines his own limits: “I have set three basic rules of painting that I always keep to: two dimensions, avoiding spatiality, plane-like surfaces.” These works – which are built of colourful, geometric elements, and lack meaning or function – may have several interpretations; Szinyova, however, leaves that completely to the viewer. He does not even try to associate additional meaning with his works by the use of titles, as he regards these works as objects without any specific meaning. No descriptive title would befit these works, but only a special code-language. As Szinyova reveals, “the titles are only abbreviations. The letters stand for the technique employed, while the numbers indicate the date when the picture was finished: day, month and year… There is no point in giving titles. These abbreviations may also be interpreted as codes. They are simply signs that facilitate the identification of the works.”

Zita Sárvári