Júlia Vécsei’s latest solo exhibition at Kisterem focuses on a fairytale world and its stories. The watercolour on paper paintings reveal suspended situations – buildings, installations, plants and translucent yellow figures in between. Some details of the magical scenes appear several times, creating associative stories as variations of each other. As in Lajos Gulácsy’s Na’Conxypán, this dream-like world is for Vécsei a representation of desolation and the exit from reality. The experiences of the last three years, the unpredictability and isolation, led Vécsei to begin working on a series of indigo drawings (Closed Spaces, 2021-2022), which dealt with the limitation of communication and the anxiety caused by the situation. After this series of monotonous, repetitive work, she created a much more intuitive, detached world in the Experimental Break series, many of whose elements were inspired by Vécsei’s dreams.

Opening: 2023. 05. 04., 18:00

Opening speech by Mária Árvai, art historian

In 1348, Florence was hit by the plague. Seven women and three men fled the plague to a country castle, where they entertained each other by telling stories for ten days. Bocaccio’s Decameron focuses on the pleasures of life on earth, with love and irony prevailing in the short stories. Júlia Vécsei’s series entitled Experimental Break has a similar framework, with drawings created in 2020-21, during the COVID pandemic, mostly in Vienna. In her case, of course, there was no large group of people retreating together, the cards were made in solitary confinement. Instead of a full-blooded Renaissance spirit, we are presented with an inner world of abstract thoughts and dreams.

Before approaching the drawings, it is worth looking at the curtains hung in front of the walls. The curtains not only decorate the interior, but also cover part of it. The fabrics create a sense of warmth and intimacy, but the slightly translucent silks that glide across the space can also be interpreted as a play of concealment/revealment, mysterious veils that hide secrets or another world.

The production and processing of textiles (yarn-making, weaving, sewing, embroidery, dyeing) is traditionally a female occupation, but this is not a nineteenth-century female art in the pejorative sense. The curtains were made in Marrakech, Morocco, in the workshop of Mancala Tissage, based on designs by Julia Vécsei, who works there. They are made of Indian silk, woven and dyed in Africa. The softly flowing, floating silks were created and carried here by crossing considerable distances, they are global products of a wide, open world.

Cyclicality is a fundamental element of womanhood, here represented as a universal cycle, in the changing of the seasons, the dark blue dyed fabric evoking night, the yellow daytime. During the pandemic, the closures disrupted the rhythm of life, the usual phases of the day shifted, merged, lengthened or shortened, the rhythm was upset. Experiences that contrasted sharply with life as it had been, and quarantine also upset our sense of reality.

This leads us to the third curtain, in which a circle of interconnected small squares appears above the yellow sunny strip, a round whole born from the addition of the parts, with different qualities from the parts. The figure is reminiscent of the monoscope, the adjustment bar broadcast during breaks in the TV broadcast, accompanied by a low-frequency beep (mostly 1 KHz). The purpose of these test bars was to help adjust sharpness, colour and sound. The curtain tunes us to the drawings, to the experimental “broadcast blackout”, where everyone in the global world is plagued by the same problem, the limitation of direct communication and human contact, the artists by the loss of exhibition opportunities, the indefinite period of blackout.

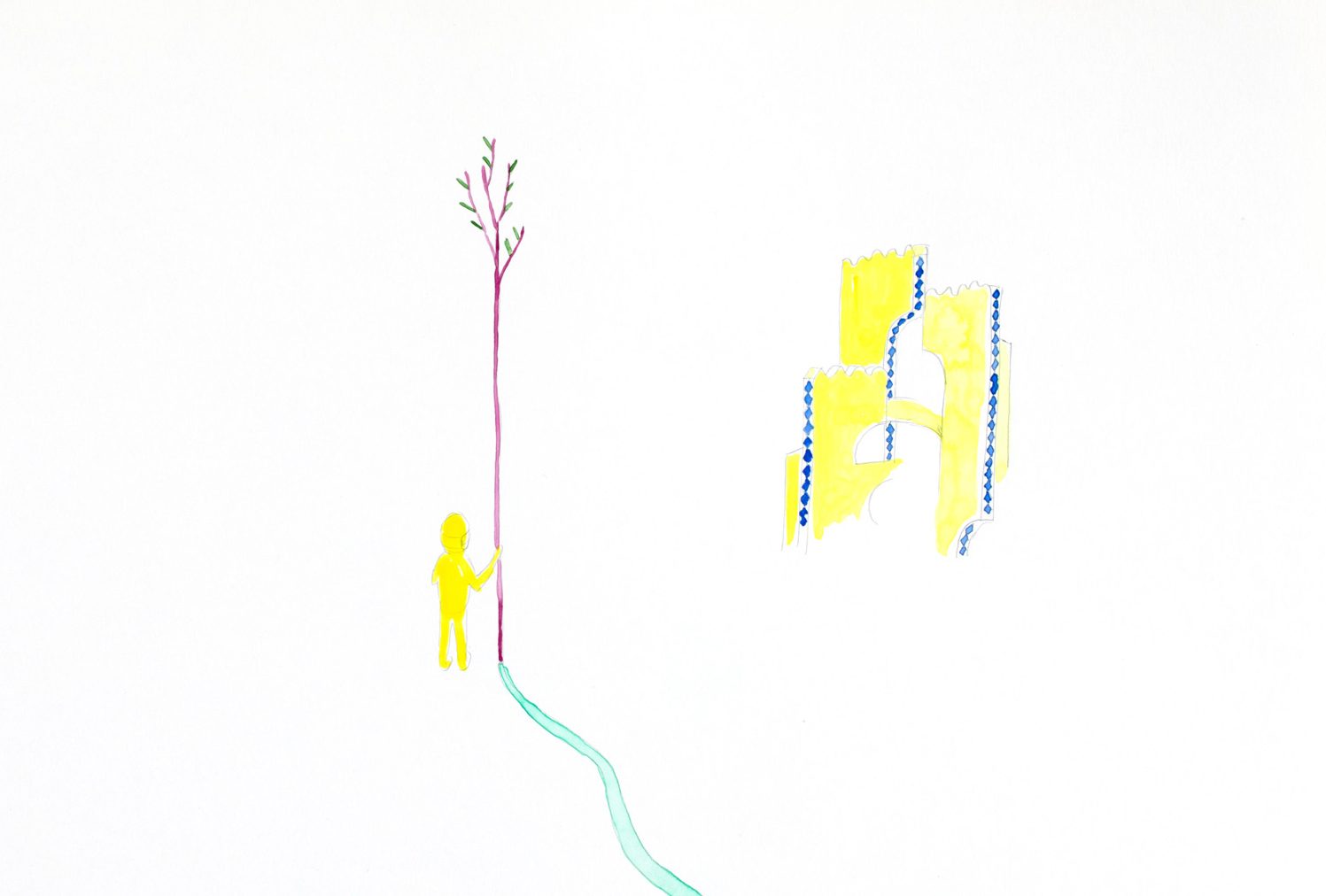

Let us approach from the drawings, watercolours. These works cause frustration in a positive sense. They promise something other than what they are. From a distance they look like cheerful, colourful drawings. Tiny figures, bright, varied colours and shapes, as if they were fairy-tale illustrations. But on closer inspection, nothing is as usual, everything is strange and tense.

They are made on light yellowish-toned paper with Japanese watercolour paints. In some places, there is also a more opaque, brightly coloured acrylic paint, while in others we find iridescent, metallic shimmering surfaces. The fragile figures are drawn with thin, supple, sweeping lines, and are characterised by a soft, personal tone and lightness. Yet where does the tension come from?

Each element is placed against a large empty background. Space is undefined, not a single horizon line is visible. The bodies have little articulation, rather their surfaces bear some kind of pattern. We see no cast shadows. There seems to be no gravity in this world. There is no need for something to hold the heavier objects, bodies, they float. Only a few motifs appear in a drawing, but their relationship to each other is often unclear, enigmatic.

Buildings, plants, fire and water dot this universe, along with tiny garish yellow figures. They resemble human figures, but are more puppet-like. They have hands and feet, but no faces, some of them wear what look like mouth masks. Poison-producing animals often wear a similar yellow colour, and this garish hue is a warning of danger. Humans are the danger, the carriers of the virus. They have little contact, not many of them are seen together. They are lonely.

At the time of the COVID-19 pandemic, the wearing of face masks was a key part of the epidemiological measures. Masks worn for preventive purposes covered most of the facial surface, significantly affecting social interaction and making it difficult to recognise and express emotions. In one drawing, the tribal masks worn by the characters show strong emotions, as was the custom in Greek theatre. Some figures hold hands, while others separate. On the cultic masks of Vécsei, there are heightened physical expressions of shock, horror and sadness. The masks contrast with the masks worn during the pandemic, masking personality and emotion, as a symbolic expression of horror at the unknown.

The images hold the promise of a narrative, but the situations are enigmatic, the story is left to the viewer to invent. Some elements are easier to decode: the lonely figure observing himself, leaning over the water, reminiscent of Narcissus; or the untruthful communication to the public in the form of the Pinocchio nose mask blaring into the funnel, but the personal content of the dreamlike installations is less accessible.

Some elements, repeated in slightly different situations, return on the pages, giving the illusion that the story is continuing. This is similar to the trickery used by Seherezade during the 1001 nights, who would interrupt a story each night to keep the curious sultan alive until the next day, waiting for the story to end. According to literary historians, the texts of the 1001 Nights have many cultural layers, with Arabic, Persian, Indian, Mesopotamian, Egyptian and European elements. Júlia Vécsei’s drawings and curtains, as well as the exhibition interior designed by the artist, also draw on her experiences in Morocco, Vienna and Hungary. In border situations, one can only find refuge in one’s inner world, the power of imagination is the key to survival.

Congratulations on the exhibition!

Mária Árvai

photography by Dávid Biró